Ah, it used to be so simple. Journalists were people who published news and information. And they abided by a code that we all understood. Independence. Editorial oversight. Objectivity.

Ah, it used to be so simple. Journalists were people who published news and information. And they abided by a code that we all understood. Independence. Editorial oversight. Objectivity.

Today, of course, that model is dead, dead, dead. Anyone can publish. But “journalistic” structures often carry some vestigal ethos from real journalism, simply by using the same structure and formatting. The web is full of this kind of almost-journalism.

Nokia published a review of its new Lumia 620 phone on the “Conversations by Nokia” blog. And guess what? They liked it! They REALLY LIKED IT.

The headline calls the phone “compact, vibrant, and lots of fun.” And then come the accolades:

“it’s clear to see that the Nokia Lumia 620 is a fun, almost-youthful smartphone, thanks to the new colour range.”

“The dual-core 1GHz Snapdragon CPU does a fantastic job at keeping everything running as smooth as any other – more expensive – smartphone.”

“If you’re into your music, you’ll be happy to know that the Nokia Lumia 620 plays it loud; at about 100db we believe. Perfect for listening to you favourite bands using Nokia Music.”

Gizmodo, AdWeek, Digiday and others had a field day with this puff piece. Giz wrote a parody review, including this bit of snark:

“The post is designed to be read as an expert review of a smartphone, aimed at helping consumers make informed purchasing decisions. It contains ample Nokia fawning cloaked in your standard gadget writer tropes, so it’s easy to confuse this public relations flackery as a real review.”

It’s instructive to read the comments on the original article. A plurality of commenters blast Nokia for publishing a deceitful article. But many others defend the company, saying of course they can write about their own product.

The takeway? The rhetorical principle at play here is ethos – the reputation of the communicator. By playing fast and loose with reader expectations, Nokia undermined its credibility. It’s essential to practice radical transparency. You’re doing yourself no good if you deceive even one reader. So, dispense with the phony review voice, clearly label third party content, and tell your story. Owned media is a powerful, often underutilized channel. Give me detailed specifications, comparisons with competing products, and detailed photos, the more the better.

Simultaneously, Nokia could also engage the social space in an ethical, open manner. Here are some things the company could legitimately do:

- Publish links to third party reviews

- Create a microsite for the product, encouraging reviews

- Create opportunities for bloggers or ordinary people to try the phone

- Lend review samples to influencers (with disclosure)

- Encourage owners to share their experiences with the phone in a wiki

- Encourage tagging of photos taken with the phone on Instagram

It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to encourage or curate social conversations about the phone. There is a catch, however: Nokia will have to respect the sentiment of the conversations. If the phone stinks, people are going to say so.

Since the social drubbing started, Nokia rewrote the headline, stating at the end of the article:

“Note: This article was first headlined as a ‘review’, obviously, it’s more of a hands-on account of Adam’s experiences and the headline has been changed to reflect that.”

Not enough. Nokia should apologize for confusing the people who read the review. And they should take it down. This is social media at its worst – people are talking, but they’re not talking about the phone. And they’re bashing your brand. Lose/lose.

Postscript: the blogger’s defense

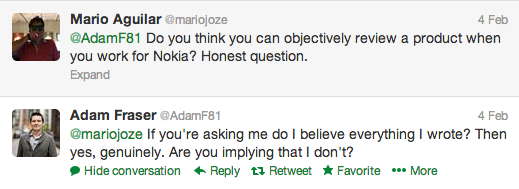

Here’s a conversation on Twitter between Gizmodo’s Mario Aguilar and review author Adam Fraser:

This sort of “statement of independence” is common in the world of the paid blogger. The author can state it repeatedly. It may be true. But it carries no credibility. The independence statement is overwhelmed by the economic arrangement.

Leave a Reply